Report on Metabolic Health and Economic Burden in Females: A Comparative Analysis

1. Executive Summary

This report provides a comprehensive analysis of metabolic health challenges and their associated economic burdens specifically concerning women, drawing parallels and distinctions with male-focused research where relevant. It highlights that while women exhibit a higher incidence of Metabolic Syndrome (MetS), they often demonstrate a lower overall all-cause mortality risk from the condition. However, a more severe progression of cardiometabolic disease (CKM syndrome) presents a disproportionately higher mortality acceleration for women. Economically, women face higher direct healthcare costs related to obesity and diabetes, despite potentially lower overall out-of-pocket expenses. Furthermore, unique factors such as pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders significantly contribute to their long-term health trajectory and associated costs. The financial investment required for women to maintain healthy lifestyles, including diet and fitness, presents a substantial economic barrier, underscoring the urgent need for gender-tailored public health strategies and policy interventions aimed at prevention and early management to mitigate escalating healthcare expenditures.

2. Introduction to Metabolic Health in Females

Overview of Metabolic Syndrome, Obesity, Hypertension, and High Cholesterol in Women

Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) is a complex cluster of interconnected risk factors, including hypertension, dyslipidemia (abnormal cholesterol levels), and elevated blood glucose, all of which significantly increase an individual's susceptibility to cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.[1] The prevalence of MetS is not uniform across the population; it varies considerably based on demographic characteristics such as age, sex, race, and ethnicity.[3]

Obesity, defined by a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 30 or higher, stands as a critical driver of numerous health complications. It substantially elevates the risk of developing a range of adverse health conditions, including high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, high cholesterol, and various forms of heart disease.[4] The escalating global prevalence of obesity underscores its status as a major public health crisis.

Recent research indicates a consistent upward trend in the incidence of MetS in both men and women. A notable observation from these studies is that women exhibit a higher incidence of MetS, with an adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) of 1.14 (95% Confidence Interval [CI], 1.05-1.24) compared to men. This suggests that women are more frequently diagnosed with this constellation of metabolic risk factors.[8] However, a compelling aspect of this finding is that despite this higher incidence, women demonstrate a significantly lower all-cause mortality risk (Hazard Ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.57-0.81) over an average follow-up period of 7.7 years when compared to men who also have MetS.8 This seemingly contradictory pattern, where a higher disease prevalence in women is accompanied by a more favorable mortality outcome, suggests that while women may be more susceptible to developing metabolic risk factors, they might possess inherent biological advantages, engage in different health-seeking behaviors, or respond differently to early disease manifestations or interventions. For instance, variations in hormonal profiles, distinct patterns of fat distribution, or a greater propensity for earlier engagement with healthcare could contribute to this observed difference in mortality, implying that the progression and severity of MetS, beyond its initial presence, may differ substantially between genders.

Contextualization of the Query within Existing Male-Focused Research

The initial inquiry that prompted this investigation primarily centered on the 20-year mortality risk associated with metabolic syndrome in males, specifically those with a BMI between 30 and 35.[1] This report directly extends that line of inquiry to females, aiming to provide a parallel, gender-specific analysis of metabolic health outcomes and their economic implications.

Many large-scale studies examining the relationship between BMI and mortality often present data aggregated across genders or focus predominantly on male cohorts.[9] This report meticulously extracts and emphasizes female-specific data, highlighting critical gender-based differences and similarities in health outcomes and economic burdens. The detailed examination presented herein aims to fill existing gaps in understanding the unique profile of metabolic health in women, offering a more nuanced perspective on how these conditions affect their longevity and financial well-being.

3. Mortality Risk and BMI in Females

Analysis of BMI Categories and their Association with All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Women

Extensive research, including a meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies involving over 30 million participants and 3.74 million deaths, provides compelling evidence that adiposity, as measured by Body Mass Index (BMI), generally increases the risk of premature mortality across the population.[9] This comprehensive analysis indicated that the lowest mortality risk was observed among participants with a BMI of approximately 25.[9]

For specific subgroups, such as never-smokers and healthy never-smokers, a J-shaped association between BMI and mortality has been consistently observed, with the lowest risk point (nadir) falling within the BMI ranges of 23-24 and 22-23, respectively. When the analysis was rigorously restricted to studies with longer follow-up durations (specifically, ≥20 or ≥25 years), a methodological approach designed to minimize confounding by pre-diagnostic weight loss, the optimal BMI range associated with the lowest mortality risk narrowed further to 20-22.[9] This underscores the critical importance of controlling for confounding factors to accurately assess the true relationship between BMI and mortality.

Focusing specifically on older adults, particularly those aged 80 years and older, a nuanced relationship between BMI and mortality emerges. In this demographic, overweight women (with a BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m²) demonstrated a reduced mortality risk (HR = 0.79, 95% CI 0.65–0.97) when compared to individuals in the normal or underweight categories. Notably, obese women (with a BMI of ≥30 kg/m²) within this same age group did not exhibit an increased mortality risk (HR = 1.03, 95% CI 0.84–1.27).[10] This contrasts with findings in men, where both overweight and moderately obese (BMI 30-34.9 kg/m²) categories were associated with a reduced mortality risk compared to normal weight men.[10] Even after adjusting for various confounders, including smoking status, education level, physical activity, and pre-existing comorbidities, overweight women continued to show a lower mortality risk (HR = 0.87, 95% CI 0.70–0.98) compared to their normal/underweight counterparts.[10]

A separate 30-year study investigating cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic (CKM) syndrome revealed that as the severity of CKM progressed, it was consistently associated with increased all-cause mortality. Importantly, this study found that the magnitudes of increased risk were notably greater in women (Hazard Ratios ranging from 1.24 to 3.33) compared to men (Hazard Ratios ranging from 0.85 to 2.60) across all stages of CKM syndrome.[12] This observation suggests that while women may experience lower overall mortality from Metabolic Syndrome (as indicated by other research), the progression to a more severe, multi-systemic CKM syndrome appears to accelerate mortality risk disproportionately for them. This pattern hints at complex underlying biological or clinical differences in how advanced cardiometabolic disease impacts women, potentially pointing to a point where initial protective factors are overwhelmed, leading to a more rapid and severe decline in health compared to men at similar advanced stages.

Comparison of Female-Specific BMI-Mortality Relationships with General or Male-Focused Findings

The concept often referred to as the "obesity paradox," where overweight or mild obesity might be associated with lower mortality, is evident in the presented data. However, this phenomenon manifests with distinct differences between genders, particularly in older populations. For older women, the potential protective effect appears largely confined to the overweight category (BMI 25-29.9). In contrast, for older men, this effect extends into the moderately obese range (BMI 30-34.9).[10] This divergence suggests that the physiological mechanisms contributing to the "obesity paradox"—such as metabolic reserve, protection against frailty, or cushioning from falls—may operate differently or have different thresholds in older women compared to men. For women, the benefits of slightly higher body mass in extreme old age might diminish or even reverse once they reach obesity, possibly due to varying patterns of fat deposition (e.g., visceral versus subcutaneous fat), distinct hormonal profiles, or the cumulative burden of comorbidities that often accompany higher grades of obesity. This highlights the necessity for highly individualized and gender-sensitive approaches to weight management in the elderly, moving beyond a universal recommendation based solely on BMI.

The reliability of observed BMI-mortality associations is highly dependent on the rigorous control of confounding factors. Studies that adequately adjusted for crucial variables such as age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity consistently demonstrated a stronger and more accurate association between BMI and mortality. Conversely, studies that did not fully account for confounding factors like pre-diagnostic weight loss (where individuals may lose weight due to underlying, undiagnosed illness) or prevalent disease (existing conditions at baseline) could bias results. Such biases might lead to an artificially U-shaped association or even suggest a "protective" effect at lower BMI ranges, which could be misleading.[9] This underscores the inherent complexity in interpreting BMI data and emphasizes the need for stringent methodological approaches in epidemiological research to ensure valid conclusions.

The comparative data on mortality risks by BMI category and CKM stage for females versus males illustrates these critical gender-specific patterns.

Table: Comparative Mortality Risks by BMI Category and CKM Stage: Females vs. Males

Note: BMI data is for individuals aged ≥80 years. CKM syndrome data is from a 30-year study across various age groups.

This table is instrumental in illustrating the complex and sometimes contrasting gender-specific patterns in metabolic health outcomes. It visually highlights how the "obesity paradox" operates with different thresholds for older men and women, with the protective effect for women being more limited to the overweight category. More critically, the table starkly demonstrates the disproportionately higher acceleration of mortality risk for women as cardiometabolic disease progresses to advanced CKM stages. This comprehensive comparison is essential for health policy analysis, as it underscores the need for targeted early interventions and gender-specific management strategies to address these distinct risk profiles.

4. Metabolic Syndrome and Life Expectancy in Females

Prevalence and Impact of Metabolic Syndrome and its Components (Diabetes, Hypertension, High Cholesterol) on Female Life Expectancy

Obesity is a well-established factor that significantly reduces life expectancy, with estimates varying from an average of 3 to 10 years, depending on the severity of the condition.[13] More specifically, moderate obesity (defined as a BMI between 30 and 35) may lead to a reduction in life expectancy of approximately three years, while severe obesity (BMI of 40 or higher) could potentially shorten an individual's life by as much as ten years.[4] A broader estimate suggests that obesity can reduce life expectancy by up to 5 years for women (and 20 years for men), contributing to an estimated 300,000 deaths annually in the U.S.[6]

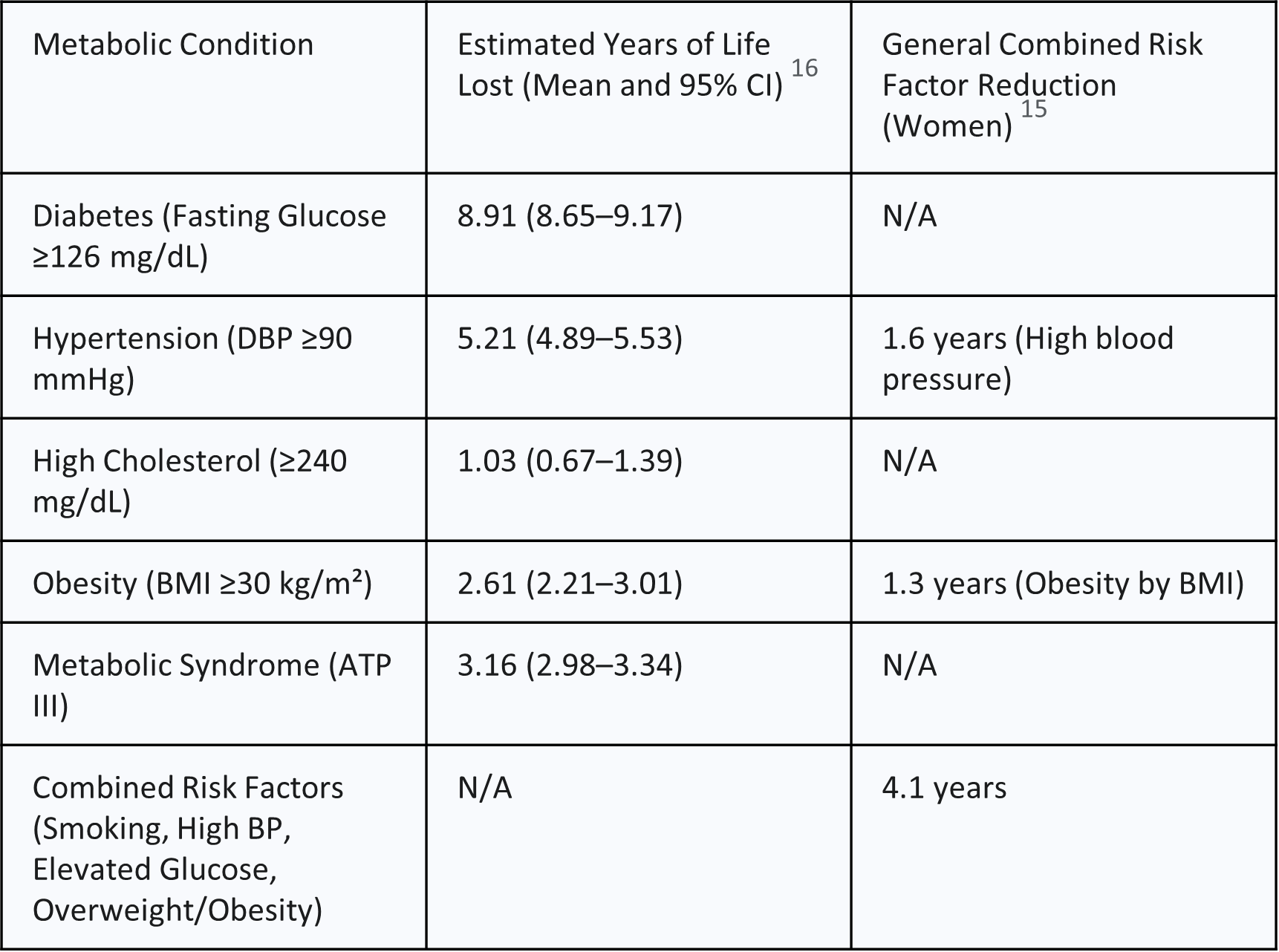

A comprehensive study estimated that the combined impact of several key risk factors—smoking, high blood pressure, elevated blood glucose, and overweight/obesity—collectively reduces life expectancy in the U.S. by 4.9 years in men and 4.1 years in women.[15] When examining the contribution of individual risk factors specifically for women, the reductions in life expectancy were estimated as follows: 1.6 years due to high blood pressure, 1.3 years due to obesity (as measured by BMI), 0.3 years due to elevated blood glucose, and 1.8 years due to smoking.[15]

More granular data on specific cardiometabolic risks provides direct quantitative estimates of years of life lost for women:

Diabetes (defined as fasting glucose ≥126 mg/dL) is associated with a loss of 8.91 years (95% CI 8.65-9.17).[16]

Hypertension (diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg) is linked to a loss of 5.21 years (95% CI 4.89-5.53).[16]

High cholesterol (total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL) is associated with a loss of 1.03 years (95% CI 0.67-1.39).[16]

Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²) is estimated to result in a loss of 2.61 years (95% CI 2.21-3.01).[16]

Metabolic Syndrome (based on ATP III criteria) is associated with a loss of 3.16 years (95% CI 2.98-3.34) for women.[16]

Type 2 diabetes, in particular, is estimated to reduce life expectancy by up to 10 years.[17]

The variability observed in the reported life expectancy reduction attributable to obesity—ranging from "as much as 5 years" [6] to "3 to 10 years depending on severity" [4], and more specific estimates like "1.3 years" [15] or "2.61 years" for BMI ≥30 [16]—can appear complex for those seeking clear guidance. This wide range of estimates likely stems from differences in study methodologies, the specific population cohorts analyzed (e.g., age groups, presence of comorbidities), the precise definition and severity of "obesity" utilized, and the statistical models applied. For instance, a "maximum" reduction might refer to cases of extreme obesity compounded by multiple severe comorbidities, whereas an "average" reduction might represent a broader obese population. For public health communication and policy development, this variability indicates that presenting a single number for life expectancy reduction due to obesity can be an oversimplification. It is more informative to present a range and contextualize these figures based on the severity of obesity and the presence of co-occurring conditions. Policy makers should understand that while obesity unequivocally reduces life expectancy, the magnitude of this impact is influenced by multiple factors, and interventions targeting specific co-occurring conditions, such as diabetes, might yield more predictable and substantial gains in life years. This also points to a need for more standardized reporting of such impacts in future research.

Discussion of how these conditions contribute to reduced longevity in women

Obesity serves as a powerful catalyst for the development and progression of numerous chronic diseases, including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain types of cancer. These conditions are primary drivers of reduced life expectancy, largely due to the severe complications they can induce.[4]

Beyond directly causing these major diseases, obesity can significantly impair respiratory function, leading to conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea, obesity hypoventilation syndrome, and exacerbated asthma. These respiratory complications further diminish overall health and contribute to reduced longevity.[4]

Furthermore, obesity profoundly disrupts the body's intricate metabolic processes. This disruption often leads to increased insulin resistance, which is a precursor to the development of full-blown metabolic syndrome and, subsequently, type 2 diabetes.[4] These metabolic dysfunctions create a cascading effect of health issues that cumulatively shorten an individual's lifespan.

When comparing the estimated years of life lost for women across various metabolic conditions, it becomes evident that diabetes accounts for a significantly greater reduction in life expectancy (8.91 years lost) compared to hypertension (5.21 years), high cholesterol (1.03 years), or even obesity itself (2.61 years).[16] This quantitative comparison highlights a clear hierarchy of impact among the core components of metabolic syndrome. This finding indicates that, for women, diabetes poses the most severe long-term threat to longevity. This elevated impact could be attributed to the systemic nature of diabetes, which can lead to widespread complications affecting multiple organ systems, including cardiovascular, renal, neurological, and ocular systems, thereby resulting in a higher cumulative burden of disease and premature mortality. The chronic nature of diabetes and the persistent challenges in maintaining optimal glycemic control over decades further compound its impact. This observation is paramount for prioritizing public health interventions and clinical management strategies aimed at improving female life expectancy. Resources and efforts should be heavily focused on diabetes prevention, early detection, and aggressive management in women. This includes promoting lifestyle changes to prevent type 2 diabetes, ensuring access to affordable medications (such as insulin, which has seen initiatives to cap costs at $35 per month for Medicare and commercially insured patients [18]), and providing comprehensive care to prevent or delay diabetes-related complications. This provides a strong rationale for investing disproportionately in diabetes-focused programs for women from both a health and economic perspective.

The following table provides a clear quantification of the estimated life expectancy reduction for women based on specific metabolic conditions.

Table: Estimated Life Expectancy Reduction by Key Metabolic Condition in Females (Years Lost)

This table is exceptionally valuable as it directly quantifies the impact of specific metabolic conditions on female life expectancy, providing concrete, actionable numbers. It moves beyond general statements to offer precise data points critical for health policy and intervention planning. By exclusively focusing on women, it directly fulfills the core requirement of the user's query. The table allows for a clear, side-by-side comparison of the relative impact of each condition, thereby informing resource allocation and highlighting which metabolic factors contribute most significantly to reduced longevity in women. This direct quantification strengthens the evidence base for targeted public health initiatives.

5. Healthcare Costs for Females with Metabolic Conditions

Detailed Breakdown of Direct Medical Expenditures (Inpatient, Outpatient, Prescription Medications) for Women with Obesity, Diabetes, Hypertension, and High Cholesterol

The financial burden of metabolic conditions on the healthcare system is substantial, with notable differences observed between genders. The average annual health care costs for an individual with a normal BMI (19) were found to be $2,368, escalating to $4,880 for a person with a BMI of 45 or greater.[19] Importantly, women in this study consistently incurred higher overall medical costs across all BMI categories compared to men, although men experienced a steeper increase in medical costs as their BMI rose.[19] An older study from 2010 estimated that obesity was associated with additional annual costs of $4,879 for a woman, in contrast to $2,646 for a man.[20] More recent data reinforces this pattern, indicating that obese women incur an extra $4,870 per year compared to women of healthy weight, while for men, this additional cost is $2,646.[21] This highlights a consistent pattern of higher obesity-related healthcare expenditures for women.

The total costs of medical care for patients diagnosed with Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) are approximately 20% higher, averaging $40,873, compared to $33,010 for those without MetS.[3] The economic burden is further amplified by costly incident complications such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and morbid obesity.[22]

Diabetes-Specific Costs: Diabetes is currently recognized as the most expensive chronic disease in the United States.[5] The total annual cost of diagnosed diabetes in 2022 was estimated at $412.9 billion, a figure that includes $306.6 billion in direct medical costs and $106.3 billion in indirect costs such as lost productivity.[23] Individuals with diagnosed diabetes incur average annual medical expenditures of $19,736, with approximately $12,022 of this amount directly attributable to diabetes. On average, their medical expenditures are 2.6 times higher than those of individuals without diabetes.[23]

For women with diabetes, unadjusted mean total expenditures were significantly higher at $12,485 compared to $10,828 for men (p=0.039).[25] In adjusted models, women consistently showed higher incremental costs ranging from $1,657 to $1,794 compared to men. However, in the final fully adjusted model, this difference, while still present ($1,314 higher for women), was no longer statistically significant (p=0.10).[25] Out-of-pocket costs for type 1 diabetes averaged $2,037 in 2018, compared to $1,122 for individuals without diabetes.[5] Glucose-lowering medications and diabetes supplies constitute approximately 17% of the total direct medical costs attributable to diabetes.[24] Regarding specific medications, the list price for Repatha, a cholesterol-lowering injectable, is $572.70 per month, though commercially insured patients may pay as little as $5 per month with a co-pay card.[26] Annual spending on statins in the U.S. is around $10 billion, with patients contributing approximately $3 billion out-of-pocket.[28]

Hypertension-Specific Costs: Annual costs associated with high blood pressure were estimated at $219 billion in the U.S. in 2019.[29] Annual medical costs for individuals with high blood pressure were $2,759 higher than for those without hypertension in 2019, and $2,926 higher for privately insured adults in 2021.[29] Individuals with hypertension generally face nearly $2,000 higher annual healthcare expenditures compared to their non-hypertensive peers.[30] In 2010, the mean expenditure per person for hypertension treatment was slightly higher for women ($751) than for men ($713).[31] A significant gender-specific cost is associated with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. Women with conditions such as preeclampsia and eclampsia, chronic hypertension, and gestational hypertension incurred substantially higher mean medical expenditures compared to women without these conditions (e.g., $9,389 higher for preeclampsia and eclampsia; $6,041 higher for chronic hypertension; $2,237 higher for gestational hypertension).[32]

High Cholesterol-Specific Costs: The annual cost of statin treatment typically ranges from $600 to $2,100 per subject, depending on LDL cholesterol levels and the specific statin prescribed.[33] The incremental cost per subject for statin treatment, which accounts for both medication and avoided major coronary events, ranges from $480 to $1,920 per year.[33] Lifetime simvastatin treatment has been shown to yield costs per life year gained ranging from $2,500 to $11,000, influenced by age and risk profile.[11]

Analysis of Out-of-Pocket Expenses and the Overall Economic Burden

The overall mean annual out-of-pocket (OOP) healthcare expenses for families in the U.S. were reported as $4,423.[34] For females, the mean OOP expenditures were $3,482, while for males, they were $5,326.[34] This broad figure encompasses various healthcare costs and is not solely confined to metabolic conditions. Medications and health insurance premiums represent the largest components of these OOP costs.[34]

A critical observation arises when comparing overall and condition-specific out-of-pocket costs for women. While women generally exhibit lower overall mean annual out-of-pocket healthcare expenses compared to men, closer examination of specific metabolic conditions reveals a different picture. Women face higher additional costs for obesity ($4,870 more per year than healthy weight women, compared to $2,646 for men) [21] and higher unadjusted mean total expenditures for diabetes ($12,485 versus $10,828 for men).[25] This pattern suggests that while women might utilize healthcare services differently or have different insurance coverage patterns that result in lower overall OOP spending, when they develop specific chronic metabolic conditions, the financial burden for managing those conditions can be disproportionately higher for them. This could be attributed to more intensive treatment protocols, longer disease duration, or a higher prevalence of certain complications in women. It implies that the seemingly "lower overall OOP" figure might mask significant financial strain directly related to specific chronic diseases. This understanding is crucial for comprehending the true financial burden on women with metabolic conditions.

Chronic diseases, including metabolic conditions, account for a vast majority (90%) of the nation's $4.5 trillion in annual healthcare expenditures.[35] The direct healthcare costs for chronic conditions totaled $1.1 trillion in 2016, an amount equivalent to nearly 6% of the nation's GDP, with diabetes identified as one of the most expensive conditions.[37] Obesity alone costs the U.S. healthcare system almost $173 billion annually.[35] Furthermore, physical inactivity contributes an additional $117 billion per year in related healthcare costs.[35]

The economic trajectory of metabolic disease reveals a compounding and potentially unsustainable burden. The sheer scale of national costs for individual metabolic conditions—diabetes at $412.9 billion [23], hypertension at $219 billion [29], and obesity at $173 billion [35]—is already staggering. More critically, projections indicate that healthcare costs associated with cardiovascular risk factors are expected to nearly triple, reaching $1.344 trillion by 2050.[39] Metabolic Syndrome itself is a cluster of these conditions, which means these costs are often overlapping and compounding, creating a multiplicative effect rather than a simple additive sum. This escalating cost suggests that the current approach to managing chronic metabolic diseases is leading to an unsustainable economic burden. Without a fundamental shift in public health strategy, particularly towards upstream prevention and early management, the economic strain on healthcare systems and national economies will become immense, potentially diverting critical resources from other essential areas. This highlights the urgent necessity for comprehensive, integrated public health strategies that prioritize the prevention of metabolic syndrome and its components, rather than solely focusing on managing established disease. Investing in population-level interventions, promoting healthy lifestyles, and ensuring early detection and aggressive management of risk factors could significantly alter this escalating cost curve. The economic argument for prevention is overwhelming, and this report provides a strong foundation for advocating for such systemic changes.

The following table summarizes the annual healthcare costs for females with key metabolic conditions, including direct and out-of-pocket expenses.

Table: Annual Healthcare Costs for Females with Key Metabolic Conditions (Direct & Out-of-Pocket)

This table is crucial because it directly quantifies the financial burden of key metabolic conditions on women, a central aspect of the user's query. By compiling direct medical and out-of-pocket costs, it provides a clear picture of the economic impact. The inclusion of comparative male data for obesity costs highlights a significant gender disparity. This table serves as a powerful tool for policy analysts to understand where healthcare spending is concentrated for women with these conditions, informing decisions on resource allocation, insurance coverage, and targeted financial support programs to alleviate the burden on individuals and the healthcare system.

6. Health Insurance and Lifestyle Costs for Females

Impact of Obesity and Chronic Conditions on Health Insurance Premiums for Women

Health insurance premiums for individuals with obesity are generally higher due to the increased risk of developing chronic conditions such as heart disease, which subsequently lead to more frequent medical interventions and higher costs for insurance providers. A high Body Mass Index (BMI) can, in some cases, result in up to a 50% loading on monthly premiums.[7]

A significant point of consideration is the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which, as of 2014, prohibits group and individual health plans from charging different premiums or denying coverage based solely on obesity or health status.[40] However, despite this federal mandate, the landscape remains complex. The same source indicates that historically, and potentially still in nuanced ways, "most states allow health plans to charge higher premiums for or decline to cover obese individuals".[40] This apparent contradiction suggests that while direct premium surcharges based solely on BMI might be restricted under ACA-compliant plans, other forms of insurance or specific state regulations might still allow for such practices. Furthermore, even if direct BMI-based surcharges are prohibited, chronic conditions frequently associated with obesity (such as diabetes or hypertension) can still influence overall healthcare costs, which in turn can affect general premium increases for all beneficiaries or the availability of certain plans. This situation reveals a complex and potentially confusing environment for women with obesity seeking health insurance. Despite federal protections, they may still encounter barriers or higher costs indirectly. This implies a need for greater transparency from insurers and continued advocacy for robust, comprehensive, and truly non-discriminatory health insurance coverage for obesity management and related chronic conditions. For policy analysts, it highlights an area where the intent of federal law may not fully translate into equitable access and affordability on the ground, warranting further investigation into state-level practices and potential loopholes.

Studies also indicate that women, compared to men, may face higher percentage increases in overall healthcare costs associated with obesity.[7] While this does not explicitly translate to higher premium surcharges specifically for women, it strongly suggests that the underlying cost burden that drives premiums is greater for them. Public opinion on BMI-based premium surcharges is divided; 48% of individuals disagreed that insurers should be able to charge more based on obesity, while 26% agreed.[40] Interestingly, overweight and obese individuals themselves were more likely to disagree with such surcharges (57% of obese individuals versus 39% of overweight individuals).[40]

Regarding chronic conditions more broadly, individuals with diabetes, while generally having higher overall health insurance coverage, were less likely to have private insurance compared to those without diabetes. Furthermore, individuals with diabetes, particularly those in lower income brackets, spent a higher proportion of their family income on out-of-pocket private insurance premiums.[41]

The average annual cost of individual health insurance in the U.S. was $8,951 in 2024, with family coverage averaging $25,572. These costs have been rising rapidly, with a 6% increase for individual plans and 7% for family plans from 2023 to 2024.[42] The average monthly premium for an individual marketplace policy was $456, and for an employer-sponsored policy, $111.[44] Age is a significant factor influencing premiums, with older individuals typically paying higher rates, capped at three times the rate for a 21-year-old.[45]

Overview of Average Annual Costs Associated with Healthy Lifestyle Choices (Diet, Vitamins, Gym Memberships) Relevant to Women's Health

The economic barrier to healthy lifestyle choices for women, and its profound long-term health implications, is a critical area of concern. Data consistently demonstrates that healthy food options are significantly more expensive; for example, Americans pay approximately 40% more for fruits and vegetables than they would in an ideally efficient market.[46] Conversely, unhealthy diets are estimated to result in an additional $50 billion in healthcare costs annually.[47]

Simultaneously, engaging in preventative healthy lifestyle choices such as maintaining a nutritious diet, regular exercise (including gym memberships and personal trainers), and even supplement use incurs substantial annual costs for women. These upfront costs are considerable, especially when juxtaposed with the higher healthcare costs women face once metabolic conditions develop (e.g., an estimated $4,870 in excess annual costs for obesity alone [21]).

This situation creates a significant economic barrier to prevention and effective management of metabolic conditions for women. The financial investment required to maintain a consistently healthy lifestyle is often prohibitive for many, particularly those in lower-income brackets (as indicated by the willingness-to-pay data for insurance benefits [40]). This financial strain can compel individuals towards cheaper, often less healthy, food options and limit access to fitness resources, thereby perpetuating a cycle of poor health and higher future medical expenses. This underscores a critical public health and economic challenge. Policies must actively address the affordability and accessibility of healthy lifestyle choices, especially for women. This could involve exploring subsidies for healthy foods, expanding access to affordable community fitness programs, or integrating comprehensive wellness benefits into health insurance plans with minimal additional cost to the individual. Reducing these upfront financial barriers is essential not only for improving individual health outcomes but also for mitigating the escalating long-term economic burden of chronic metabolic diseases on the healthcare system and society as a whole. The low willingness to pay extra for wellness benefits [40] further reinforces the need for external support or different incentive structures to promote preventative health behaviors.

Diet Costs:

The average cost of groceries in America in 2024 was $418.44 per person per month, equating to approximately $5,021 annually.[48] A separate estimate for food-secure individuals in 2023 indicated a national average cost per meal of $3.58, translating to about $325.78 per month or $3,909 annually.[49] Following healthy dietary guidelines, such as the MyPlate Dietary Guidelines, can cost a family of four between $12,000-$14,400 annually.[50]

For a single adult female aged 20-50 years, the USDA Food Plans for May 2025 provide specific monthly costs. After applying the recommended +20% adjustment for a single-person household [51]:

Thrifty Plan: ~$297.36/month or ~$3,569 annually (based on $247.80/month from [51]).

Low-Cost Plan: ~$319.32/month or ~$3,832 annually (based on $266.10/month from [53]).

Moderate-Cost Plan: ~$389.04/month or ~$4,668 annually (based on $324.20/month from [53]).

Liberal Plan: ~$495.72/month or ~$5,948 annually (based on $413.10/month from [53]).

Vitamin/Supplement Costs:

Americans spend an average of $510 annually on vitamins or supplements.[54] For older adult dietary supplement users, the mean annual cost burden was $186 per person, with increased spending on supplements associated with female gender, older age, and higher income.[55] Specifically, the mean monthly cost for females was $13.55, compared to $9.60 for males, translating to approximately $162.60 annually for females.[55]

Gym Membership/Personal Trainer Costs:

Gym memberships in the U.S. generally range from $20 to $60 per month, or $240 to $720 annually.[56] The average cost is around $58 per month, equating to approximately $696 annually.[57] Women-only gyms typically range from $30 to $80 per month, or $360 to $960 annually.[58] Personal trainers typically charge $40-$70 per session, with monthly packages averaging $250-$400.[59] Annually, this could range from $3,000 to $4,800. Another source estimates costs between $300-$600 per month, or $3,600-$7,200 annually.[60]

The following table provides a summary of average annual lifestyle-related costs for females.

Table: Average Annual Lifestyle-Related Costs for Females (Diet, Supplements, Fitness) in 2025

This table is highly valuable because it quantifies the financial commitment required for women to adopt and maintain a healthy lifestyle, which is a cornerstone of preventing and managing metabolic conditions. By presenting various cost tiers for diet and fitness, it acknowledges diverse socioeconomic realities. This data is crucial for informing policy discussions about making healthy choices more economically feasible and accessible. It highlights the significant upfront investment needed, thereby strengthening the argument for public health initiatives, subsidies, or insurance reforms that reduce these barriers and promote long-term health and economic benefits.

7. Key Gender-Specific Insights and Disparities

Synthesis of Significant Differences and Similarities in Health Outcomes and Economic Burdens between Females and Males

An analysis of the available data reveals both commonalities and distinct differences in metabolic health outcomes and economic burdens between females and males.

Similarities:

BMI and Mortality: For both genders, a general association exists between higher BMI and an increased risk of all-cause mortality. However, the specific BMI ranges associated with the lowest risk can vary based on confounding factors and the duration of follow-up in studies.[9]

Metabolic Syndrome Mortality Trends: Overall, a positive trend of decreasing mortality rates from Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) has been observed for both men and women over time, suggesting improvements in diagnosis and management strategies.[8]

Obesity and Life Expectancy: Obesity consistently contributes to a reduction in life expectancy for individuals of both sexes.[4]

Increased Costs with Conditions: Both men and women experience increased healthcare costs when affected by metabolic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and high cholesterol.[3]

Differences:

MetS Incidence vs. Mortality: Women exhibit a higher incidence of MetS compared to men. Yet, paradoxically, they experience a lower overall all-cause and cardio-cerebrovascular mortality from MetS over a medium-term follow-up period.[8] This suggests that while women may be more prone to developing the syndrome, factors related to disease progression or resilience may differ.

BMI-Mortality Paradox in Older Adults: In individuals aged 80 years and older, the "obesity paradox"—where higher BMI is associated with lower mortality—manifests differently. For women, this potential protective effect is primarily observed in the overweight category (BMI 25-29.9), whereas for men, it extends to both overweight and moderately obese categories (BMI 30-34.9).[10] This indicates distinct physiological responses to body fat in later life.

Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic (CKM) Syndrome Severity: Women experience a greater magnitude of increased mortality risk across advancing stages of CKM syndrome compared to men.[12] This contrasts with the overall lower MetS mortality in women, suggesting a critical point of divergence as metabolic disease progresses to more severe, multi-systemic involvement.

Obesity-Related Healthcare Costs: Obesity is associated with significantly higher additional annual healthcare costs for women ($4,870) compared to men ($2,646).[21] Furthermore, women generally incur higher overall medical costs across all BMI categories.[19]

Diabetes-Related Healthcare Costs: Women with diabetes have demonstrated higher unadjusted mean total healthcare expenditures ($12,485) compared to men ($10,828).[25]

Hypertension Treatment Costs: The mean expenditure for hypertension treatment was slightly higher for women ($751) than for men ($713) in 2010.[31] Critically, women with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (e.g., preeclampsia) incur substantially higher medical expenditures, representing a unique and significant cost driver for female health.[32]

Overall Out-of-Pocket (OOP) Costs: While females generally report lower overall mean annual OOP healthcare expenses ($3,482) compared to males ($5,326) [34], this broad figure may not fully capture the disproportionately higher condition-specific financial burdens they face for conditions like obesity and diabetes.

Vitamin/Supplement Spending: Increased spending on dietary supplements is associated with female gender.[55]

Discussion of Unique Factors Influencing Female Metabolic Health and Associated Costs

Several factors uniquely influence female metabolic health and its associated economic burden.

Pregnancy-Related Metabolic Conditions: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, such as preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, are conditions exclusive to women that significantly increase medical expenditures during pregnancy and delivery.[32] These conditions are not isolated events; they are also well-established risk factors for the subsequent development of chronic hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome later in life. This creates a distinct and often more complex long-term health and economic trajectory for women, necessitating specialized long-term follow-up and preventative care that is not typically relevant for men.

Hormonal and Biological Differences: The observed pattern of higher MetS incidence but lower overall mortality in women, coupled with a more rapid acceleration of mortality risk in advanced CKM syndrome compared to men, points to fundamental biological and hormonal differences. Women might possess inherent protective mechanisms or different disease phenotypes in the early stages of metabolic dysfunction. However, once the disease progresses to a severe, multi-organ system involvement (CKM syndrome), these protective factors may be overwhelmed, leading to a more rapid and severe decline in health compared to men at similar advanced stages. This highlights the importance of early and aggressive intervention for metabolic risk factors in women to prevent progression to severe CKM syndrome. If women face a steeper mortality curve at advanced stages, then primary and secondary prevention efforts become even more vital. This also calls for further research into sex-specific pathways of disease progression and the development of gender-tailored diagnostic and prognostic tools for CKM syndrome, particularly to identify women at high risk of rapid progression.

Behavioral and Socioeconomic Factors: The data indicates that while women may have lower overall out-of-pocket healthcare expenses, they face disproportionately higher condition-specific costs for managing obesity and diabetes. This suggests that financial burdens, though potentially structured differently, remain significant for women with chronic metabolic conditions. Furthermore, the economic barrier to adopting and maintaining healthy lifestyle choices, such as purchasing healthy food and accessing fitness resources, is substantial. Healthy food options are often more expensive, and the upfront costs of preventative measures can be prohibitive for many. This financial strain can inadvertently push individuals towards less healthy, more affordable options, perpetuating a cycle of poor health and increased future medical expenses. This underscores the need for policies that actively address the affordability and accessibility of healthy lifestyle choices, especially for women, to mitigate the long-term economic burden of chronic metabolic diseases.

8. Conclusions

This comprehensive analysis of metabolic health in females reveals a complex interplay of physiological, clinical, and socioeconomic factors that differentiate their experience from that of males. While women demonstrate a higher incidence of Metabolic Syndrome, they exhibit a lower overall mortality risk from the condition compared to men. This apparent "gender paradox" warrants further investigation into potential protective mechanisms or differential disease progression pathways in women. However, this favorable overall mortality trend is nuanced; as cardiometabolic disease advances to more severe stages, women face a disproportionately higher acceleration of mortality risk, emphasizing the critical importance of early and aggressive intervention.

Economically, women bear a significant burden. They incur higher direct healthcare costs related to obesity and diabetes, despite potentially lower overall out-of-pocket expenses, suggesting that condition-specific financial strains are particularly pronounced. Furthermore, unique physiological events such as pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders introduce distinct and substantial healthcare expenditures, contributing to a complex long-term health and economic trajectory for women.

The financial investment required for women to adopt and maintain healthy lifestyles, encompassing nutritious diets, vitamin supplementation, and fitness activities, presents a considerable economic barrier. This upfront cost can inadvertently contribute to a cycle of poorer health outcomes and escalating future medical expenses.

In conclusion, understanding these gender-specific differences is paramount for developing effective public health strategies and clinical guidelines. A one-size-fits-all approach to metabolic health is insufficient. Instead, interventions must be gender-tailored, focusing on:

Early Detection and Aggressive Management: Prioritizing early diagnosis and robust management of metabolic risk factors in women, particularly to prevent progression to severe cardiometabolic disease where mortality risk accelerates sharply.

Targeted Financial Support: Addressing the disproportionately higher condition-specific healthcare costs for women with obesity and diabetes through enhanced insurance coverage or financial assistance programs.

Promoting Affordable Healthy Lifestyles: Implementing policies that reduce the economic barriers to healthy food choices and accessible fitness resources, recognizing that investing in prevention can significantly mitigate the unsustainable long-term economic burden of chronic metabolic diseases on the healthcare system.

Further research is needed to elucidate the underlying biological and behavioral factors contributing to these gender-specific patterns, ultimately informing more precise and impactful health policies.

Works cited

Metabolic Syndrome, Obesity, and Mortality | Diabetes Care, accessed July 15, 2025, https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/28/2/391/24045/Metabolic-Syndrome-Obesity-and-MortalityImpact-of

Metabolic Syndrome: What It Is, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment - Cleveland Clinic, accessed July 15, 2025, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/10783-metabolic-syndrome

Annual Medical Costs for Patients with and without Each Metabolic ..., accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Annual-Medical-Costs-for-Patients-with-and-without-Each-Metabolic-Syndrome-Component-by_tbl2_49691361

The Impact of Obesity on Life Expectancy - SAMA Bariatrics, accessed July 15, 2025, https://samabariatrics.com/the-impact-of-obesity-on-life-expectancy/

High out-of-pocket costs hindering treatment of diabetes, accessed July 15, 2025, https://ihpi.umich.edu/news-events/news/high-out-pocket-costs-hindering-treatment-diabetes

Obesity — Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments | Penn Medicine, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.pennmedicine.org/conditions/obesity

Can BMI Increase the Cost of Your Health Insurance? | LUMA, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.lumahealth.com/health-insurance/learn/can-bmi-increase-cost/

Incidence and long-term specific mortality trends of metabolic syndrome in the United States, accessed July 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9886893/

BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 - The BMJ, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/353/bmj.i2156.full.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3UziUstPADj5tnIc46ctLJ4K_Uo8Kj6eMDxiWUyatIG3gHihoN7kypBHc

Mortality risk relationship using standard categorized BMI or knee-height based BMI – does the overweight/lower mortality paradox hold true?, accessed July 15, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11001730/

Statin Cost-Effectiveness in the United States for People at Different Vascular Risk Levels, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/circoutcomes.108.808469

Sex Differences in Cardiovascular-Kidney-Metabolic Syndrome: 30-Year US Trends and Mortality Risks—Brief Report | Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology - American Heart Association Journals, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.321629

Trends in direct health care costs among US adults with ..., accessed July 15, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11232126/

Obesity - NHS, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/obesity/

Four preventable risk factors reduce life expectancy in US and lead to health disparities, study finds | ScienceDaily, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/03/100322211829.htm

Converting health risks into loss of life years - a paradigm shift in clinical risk communication, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.aging-us.com/article/203491/text

Diabetes Life Expectancy - Type 1 and Type 2 Life Expectancy, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.diabetes.co.uk/diabetes-life-expectancy.html

Insulin Cost & Affordability | ADA - American Diabetes Association, accessed July 16, 2025, https://diabetes.org/tools-resources/affordable-insulin

Health Care Costs Steadily Increase With Body Mass, accessed July 15, 2025, https://globalhealth.duke.edu/news/health-care-costs-steadily-increase-body-mass-0

Costs of Obesity - STOP Obesity Alliance - The George Washington University, accessed July 16, 2025, https://stop.publichealth.gwu.edu/sites/g/files/zaxdzs4356/files/2022-06/fast-facts-costs-of-obesity.pdf

The Cost of Obesity: a Higher Price for Women—and Not Just in Terms of Health, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.center4research.org/cost-obesity-higher-price-women-not-just-terms-health/

Longitudinal economic burden of incident complications among metabolic syndrome populations - PubMed, accessed July 15, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38987782/

New American Diabetes Association Report Finds Annual Costs of Diabetes to be $412.9 Billion, accessed July 15, 2025, https://diabetes.org/newsroom/press-releases/new-american-diabetes-association-report-finds-annual-costs-diabetes-be

Economic Costs of Diabetes in the U.S. in 2022 - PubMed, accessed July 15, 2025, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37909353/

Differences in Medical Expenditures for Men and Women with Diabetes in the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2008–2016, accessed July 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7784825/

Repatha® (evolocumab) Cost and Co-Pay Card Information, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.repatha.com/repatha-cost

How Expensive Are Cholesterol Injections? - Healthline, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/cholesterol-injection-cost

Statin statistics 2025 - SingleCare, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.singlecare.com/blog/news/statin-statistics/

Health and Economic Benefits of High Blood Pressure Interventions - CDC, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/priorities/high-blood-pressure.html

Trends in Healthcare Expenditures Among US Adults With Hypertension: National Estimates, 2003–2014 | Journal of the American Heart Association, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/jaha.118.008731

STATISTICAL BRIEF #404: Expenditures for Hypertension among Adults Age 18 and Older, 2010: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st404/stat404.shtml

Medical expenditures for hypertensive disorders during pregnancy that resulted in a live birth among privately insured women, accessed July 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10423979/

Cost Effectiveness of Statin Therapy for the Primary Prevention of Major Coronary Events in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes, accessed July 16, 2025, https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/26/6/1796/26388/Cost-Effectiveness-of-Statin-Therapy-for-the

Out‐of‐Pocket Annual Health Expenditures and Financial Toxicity From Healthcare Costs in Patients With Heart Failure in the United States - PMC, accessed July 15, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8483501/

Fast Facts: Health and Economic Costs of Chronic Conditions - CDC, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Trends in health care spending | Healthcare costs in the US - American Medical Association, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.ama-assn.org/about/ama-research/trends-health-care-spending

The Costs of Chronic Disease in the U.S. - Milken Institute, accessed July 16, 2025, https://milkeninstitute.org/content-hub/research-and-reports/reports/costs-chronic-disease-us

About Obesity - CDC, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/php/about/index.html

Forecasting the Economic Burden of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in the United States Through 2050: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001258

Insurance Coverage for Weight Loss: Overweight Adults' Views - PMC, accessed July 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3671931/

Health Insurance and Diabetes - NCBI, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK597725/

How Much Does Health Insurance Cost In The USA? - William Russell, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.william-russell.com/blog/health-insurance-usa-cost/

Section 1: Cost of Health Insurance - 10480 - KFF, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.kff.org/report-section/ehbs-2024-section-1-cost-of-health-insurance/

How Much Does Health Insurance Cost? - Ramsey Solutions, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.ramseysolutions.com/insurance/how-much-does-health-insurance-cost

Average Health Insurance Rates by Age | SmartFinancial, accessed July 16, 2025, https://smartfinancial.com/average-health-insurance-costs-by-age

The High Cost of Healthy: How Grocery Prices Shape American Diets and Health, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/the-high-cost-of-healthy-how-grocery-prices-shape-american-diets-and-health

How Much More Expensive is Healthy Food in Every State - online doctor at PlushCare, accessed July 15, 2025, https://plushcare.com/blog/how-much-more-expensive-healthy-food-every-state

The Average Cost of Food in the US - Move.org, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.move.org/the-average-cost-of-food-in-the-us/

Map the Meal Gap 2025 - Feeding America, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2025-05/Map%20the%20Meal%20Gap%202025%20Report.pdf

Does Healthy Eating Cost More? | USU, accessed July 15, 2025, https://extension.usu.edu/nutrition/research/does-healthy-eating-cost-more

Cost of Food TFP May 2025, accessed July 16, 2025, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/cnpp-costfood-TFP-may2025.pdf?itid=lk_inline_enhanced-template

Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Three Levels: Low, Moderate, Liberal; January 2025, accessed July 16, 2025, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/Cost_Of_Food_Low_Moderate_Liberal_Food_Plans_January_2025.pdf

Official USDA Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Three Levels, US Average, May 2025 1, accessed July 16, 2025, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/cnpp-costfood-3levelsTFP-may2025.pdf

The Medical Minute: Vitamin supplements versus a balanced diet? No contest - Penn State Health News, accessed July 16, 2025, https://pennstatehealthnews.org/2024/03/the-medical-minute-vitamin-supplements-versus-a-balanced-diet-no-contest/

Examining the cost burden of dietary supplements in older adults: an analysis from the AAA longroad study - PMC - PubMed Central, accessed July 16, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11909978/

How Much is a Gym Membership In 2024? - ReliaBills, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.reliabills.com/blog/how-much-is-a-gym-membership/

28 Gym Membership Statistics: Average Cost of Memberships - Renew Bariatrics, accessed July 16, 2025, https://renewbariatrics.com/gym-membership-statistics/

How Much Do Gym Memberships Cost in 2024? - WodGuru, accessed July 16, 2025, https://wod.guru/blog/average-gym-membership-cost/

How much should you budget for a personal trainer? - 9 minutes - Trainwell, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.trainwell.net/blog/how-much-does-a-personal-trainer-cost

How Much Does a Personal Trainer Cost? - Michigan Fitness Association, accessed July 16, 2025, https://mfafit.org/how-much-does-a-personal-trainer-cost/

Prevalence of obesity-related multimorbidity and its health care costs among adults in the United States | Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2025.31.2.179

Inadequate Insurance Coverage for Overweight/Obesity Management, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.ajmc.com/view/inadequate-insurance-coverage-for-overweight-obesity-management